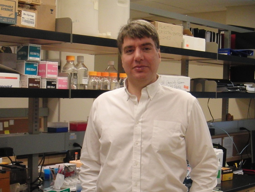

Many people wince when they get their flu shot, but for the 30 million people in the US with diabetes, injections can be a daily reality. However, one researcher at UMKC’s School of Pharmacy, Dr. Simon Friedman, is hoping to change that.

Diabetics are unable to produce or use the proper amount of insulin, a chemical that controls how your body regulates blood sugar. When left untreated, they are at severe risk of kidney failure, blindness, or loss of limbs. Today, diabetes is the seventh-leading cause of death in the U.S.

In order to bring their insulin levels back to normal, many diabetics need to take insulin injections, use an insulin pump (a device that automatically adds insulin to the body), an inhaler or a pen that shoots insulin into the skin without a needle.

Friedman saw a problem with these methods.

“One of the challenges of insulin is that its requirements are highly variable throughout the day, which is different from most drugs,” he says. “You can’t just take a pill at the beginning of the day and have it last through the whole day.”

Friedman, a biochemist, was conducting research on the interaction of large molecules with light. After gaining expertise in this area, he came to the realization that his studies could be used to change the way diabetics receive insulin.

Instead of receiving multiple injections a day or wearing an insulin pump, Friedman proposed that a polymer containing insulin could be injected into the skin of a diabetic person. When exposed to concentrated light from a device of his own lab’s creation, insulin would be released from the polymer. By merely varying the amount of light from the device, the release of insulin could tightly controlled.

The benefit? The polymer could contain enough insulin to last anywhere from a week to a month, saving diabetics from a multitude of injections. Additionally, controlled flow of insulin could be better able to tailor itself to the specific needs of a person.

After testing his hypothesis, Friedman is pleased with the progress so far.

“It’s one thing to have an idea; it’s another thing to show it in the test tube; it’s a much higher test tube to show it in vivo—in a living diabetic animal. But we’ve done that,” he says. “It’s working at every challenge we’ve thrown at the method.”

In practice, the process would be relatively simple for those receiving treatment. After the polymer is injected into the skin, they would wear an armband containing a device the size of a quarter, which would control the insulin. While Friedman is passionate about the advantages of his new technological developments, some, such as diabetic Emma Van Deventer, disagrees.

While Freidman has presented insulin injections as a painful process, Van Deventer actually chooses them over other delivery methods.

“I’ve never really had an issue with injections. They’re pretty easy to do, and they don’t actually hurt unless you’re only using one spot over and over again,” says Van Deventer.

Additionally, Van Deventer does not believe that the diabetic community at large is in need of the new device.

“I’ve been going to a diabetic camp since I was five and continue volunteering every summer as an adult, so I am very involved in seeing other people’s experiences with diabetes, and to still be on injections as a type one diabetic is super rare. Almost everyone has a pump or the insulin you can inhale, if they can afford it,” she says.

Others have been more enthusiastic about his work. UMKC Chancellor Mauli Agrawal praised Friedman’s research, calling it “exceptional work that can totally transform.” Friedman’s work with insulin delivery has also been featured in several scientific journals.

While Friedman’s project continues to be developed, it has not yet been tested on humans. He plans to continue his research as long as he can find the funding.

“We’ll keep going as long as we can get interested groups to support the work,” Friedman says.

samuelbellefy@mail.umkc.edu